FontLab in 8 days — Day 3: Beyond A-B-C¶

More glyphs & languages with FontLab 8¶

We’ve seen that fonts can contain as few characters as you want. But they can also hold tens of thousands of glyphs. What if the user needs a Euro symbol (€) and your font doesn’t have one? They could substitute the Euro from a different font, but that would look inconsistent. The better solution: add a Euro symbol to your font.

FontLab makes it easy to expand your fonts in useful ways. Three common areas are: composite characters (characters which have multiple pieces), non-alphabetic characters (like € for the Euro or ¥ for the Yen), and alternate glyphs (multiple variations of the same character). Let’s look at some examples.

English uses the basic A-Z alphabet, uppercase and lowercase. But most other Latin-script languages, like French, Czech, Spanish or German, use accented letters like àčñü. These employ diacritics — small marks that are added to the base letters. Diacritical marks are also intrinsic to many other writing systems: Greek, Arabic, Devanagari or classical Hebrew. Kanji glyphs are composed of strokes, many of which are the same or similar. In all these cases, you can build new characters by combining components.

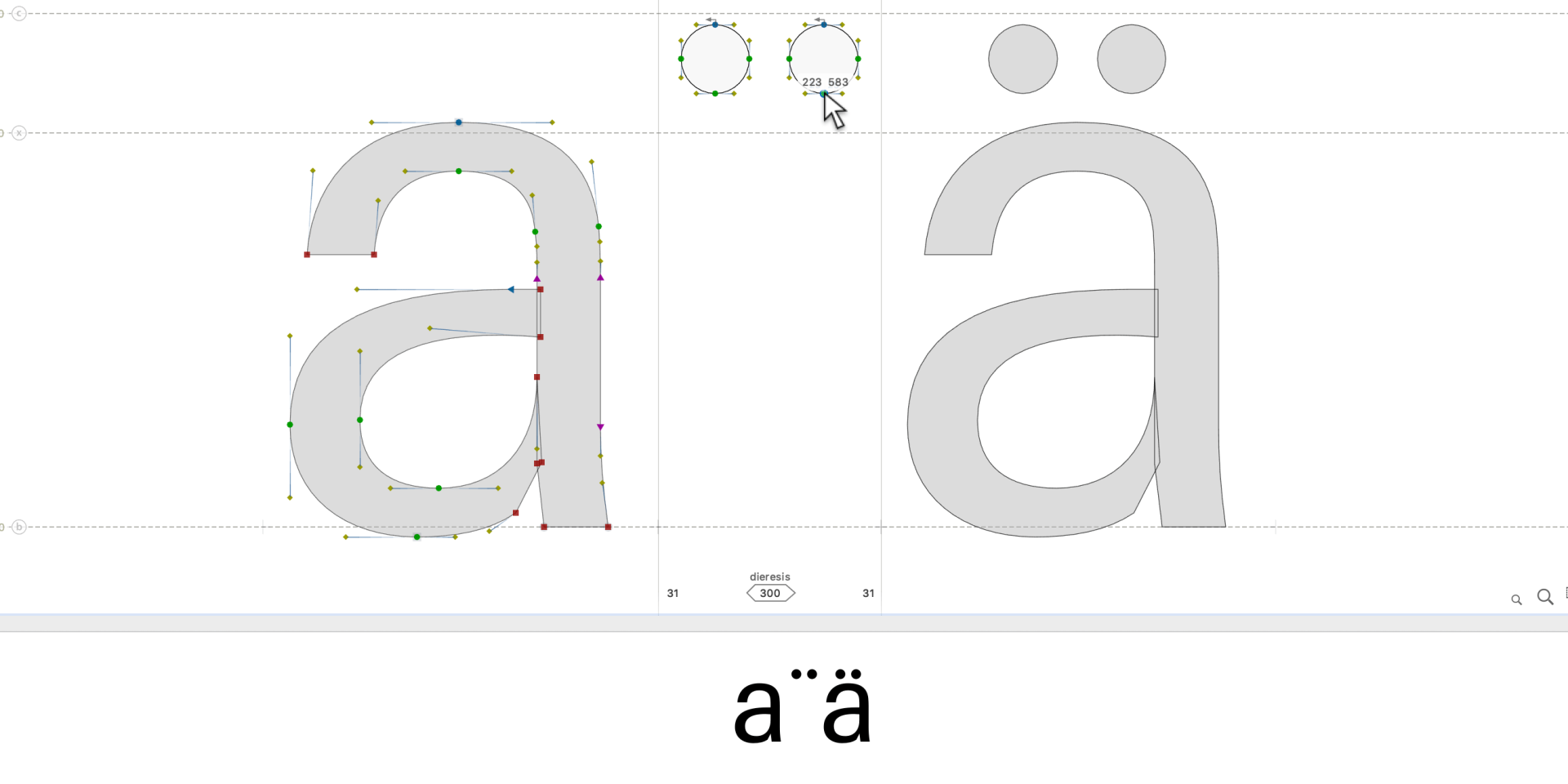

For instance, in a European font, you could draw a diaeresis once and combine it with an “a” to create “ä”. Include a set of diacritical marks, and with just one click in FontLab, add all composite letters for European and other languages.

Every unique character in the world has a dedicated code in the Unicode standard. € has the code U+20AC, and FontLab provides a slot for it. You just need to draw the shapes: combine the letter “C” and the “=” sign, then modify the glyph to be as wide as the “$” or the digit “0”.

What about symbols that don’t have Unicode codepoints?

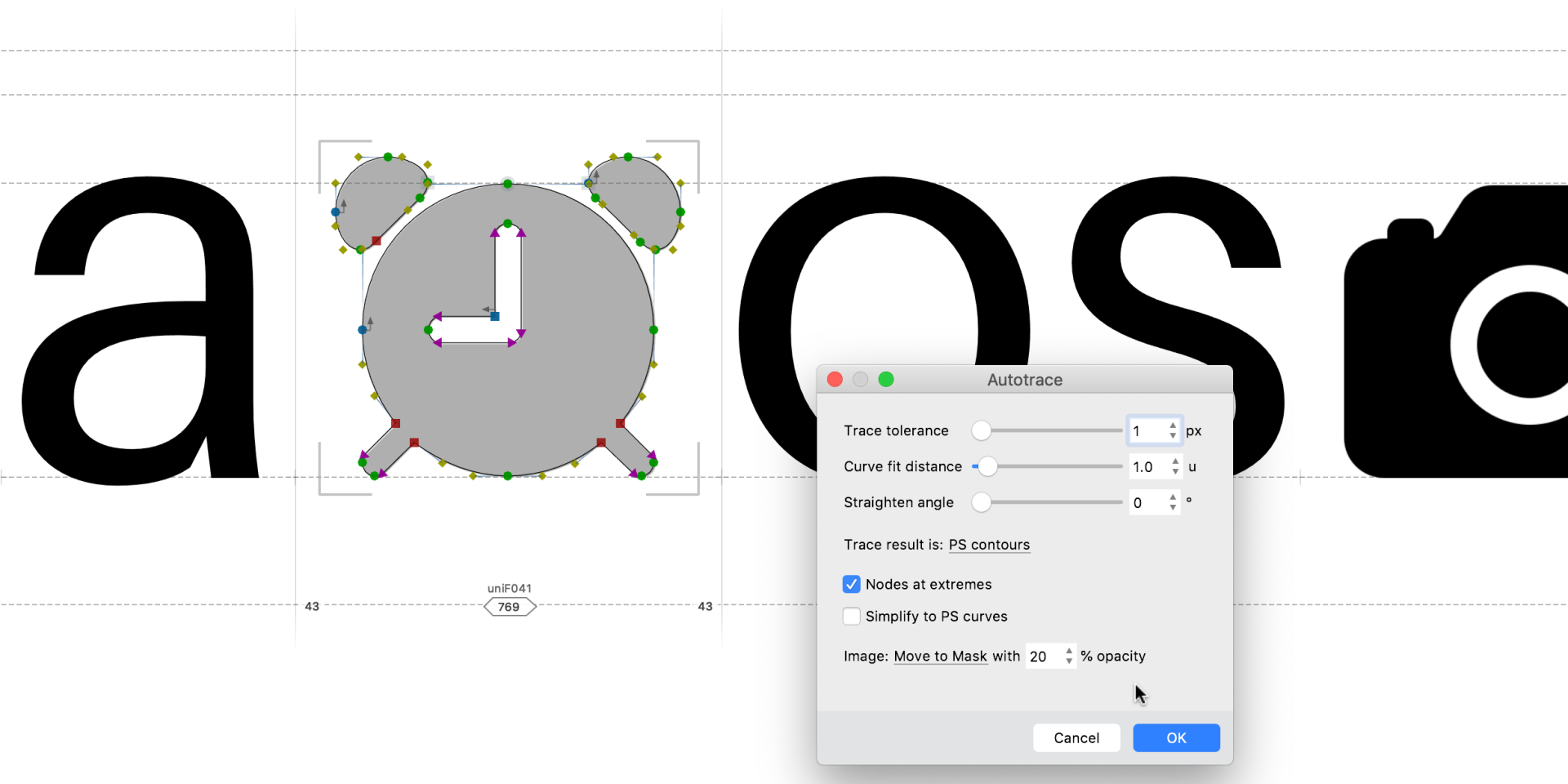

Perhaps the website, book or magazine you’re working on often includes little graphical symbols, or you’d like to simply have a scalable version of your company logo that works in all apps. These symbols aren’t “text characters”, so they don’t have unicodes, yet fonts are a great way to store and use them! You can add them to an existing font under Private Use Area unicodes (from E000 to F0FF). Better still, make a “Symbol font” and you’ll be able to type the Unicode F041 with the key A, F042 with B and so on.

Adding symbol glyphs in FontLab is a snap: copy-paste a symbol from a vector drawing app like Adobe Illustrator or Affinity Designer, or from an image editor like Photoshop. And if you give your files appropriate names, you can even drag-drop many images at once, and turn them into smooth scalable contours with Autotrace.

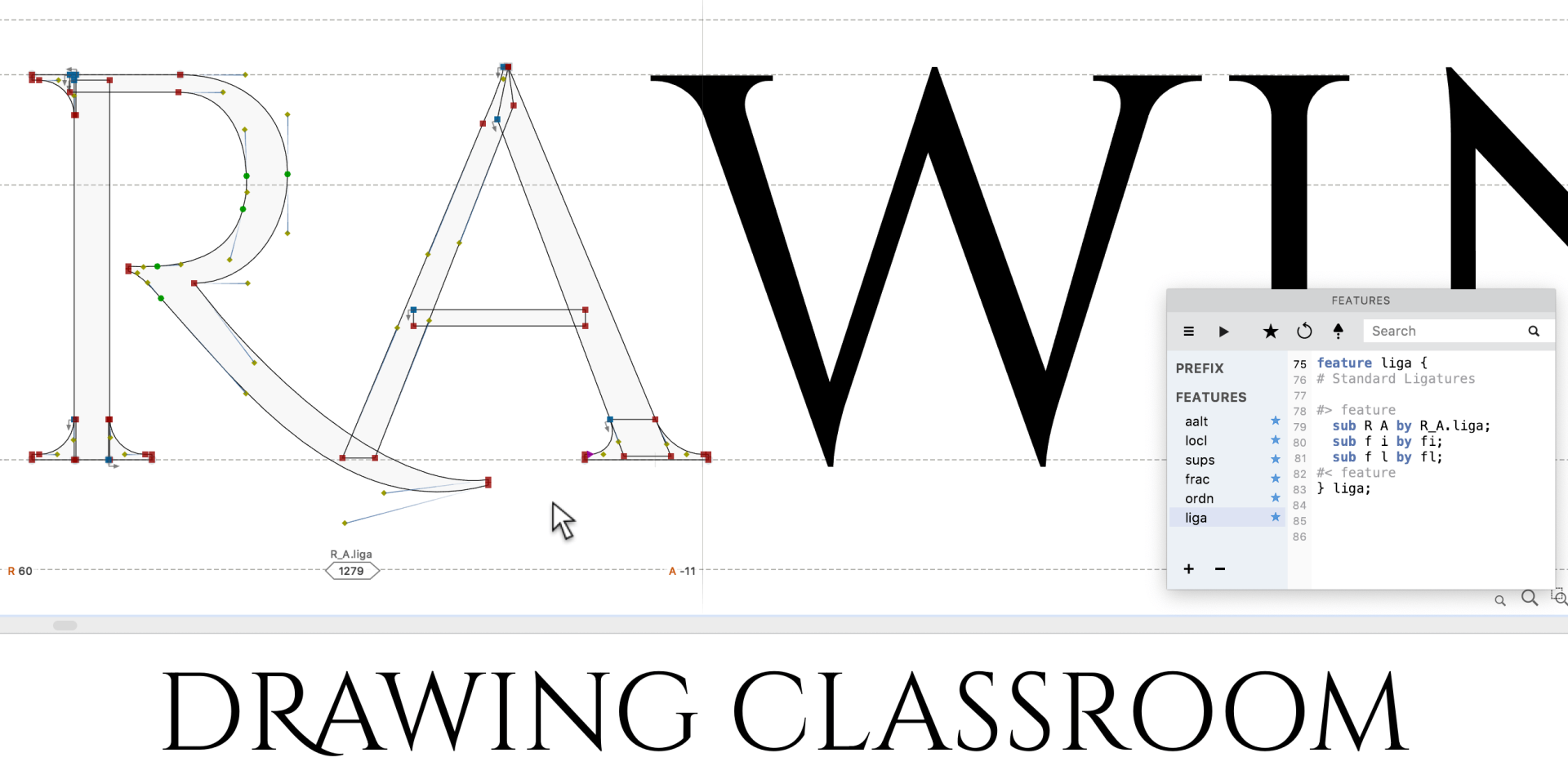

Typeface designers like to create fonts with alternate glyph variants. Let’s say you want an “R” and “A” that join nicely together. Create a special ligature glyph named “R_A.liga”, and FontLab will build the magic OpenType feature code that makes the ligature appear automatically in modern apps whenever the user types “RA”.

You can even make such automatic substitutions context-dependent, so different versions of a letter appear before or after certain other letters. Type designers have used this technique extensively for handwriting and script fonts.

With a few simple FontLab techniques, you can make a font almost infinitely extensible and expressive.

Make your (diacritical) mark with FontLab 8¶

Ever wonder what all those little marks are: ° ¨ ̴¯ ´ ¸ ˇ ˋ ˘ ˜̑͒? “Diacritics” (or “diacritical marks”, or simply “marks”) are not often seen in English, but they’re common and essential in many other languages that use the Latin script. The original Latin alphabet was made for the ancient Romans but was adapted by languages that have sounds Latin didn’t, like Spanish “ñ” and German “ü”. Some languages like to hint to know which syllable carries the stress, to make pronunciation easier: South Americans say “Panamá”, stressing the last syllable, unlike most Spanish words, so the accent reminds us of this.

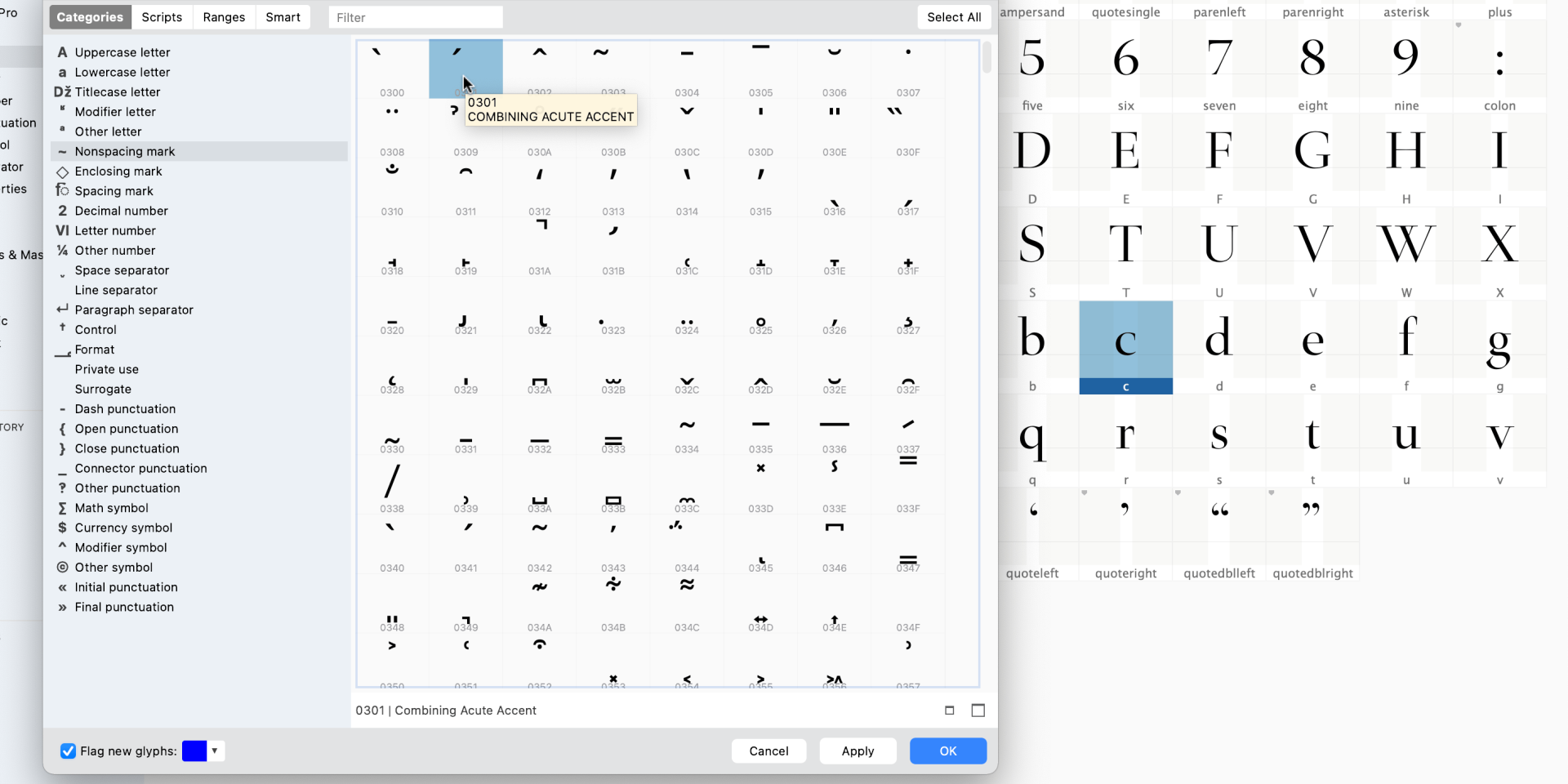

Need a diacritic that your font is missing? Open the font in FontLab, and add a new glyph for the diacritic mark: Choose Font > Add Glyphs, select the Nonspacing Mark category, click the cells for the marks you need, OK. Double-click the added glyph cell and draw the mark. Diacritics have simple shapes, so this should only take a few minutes.

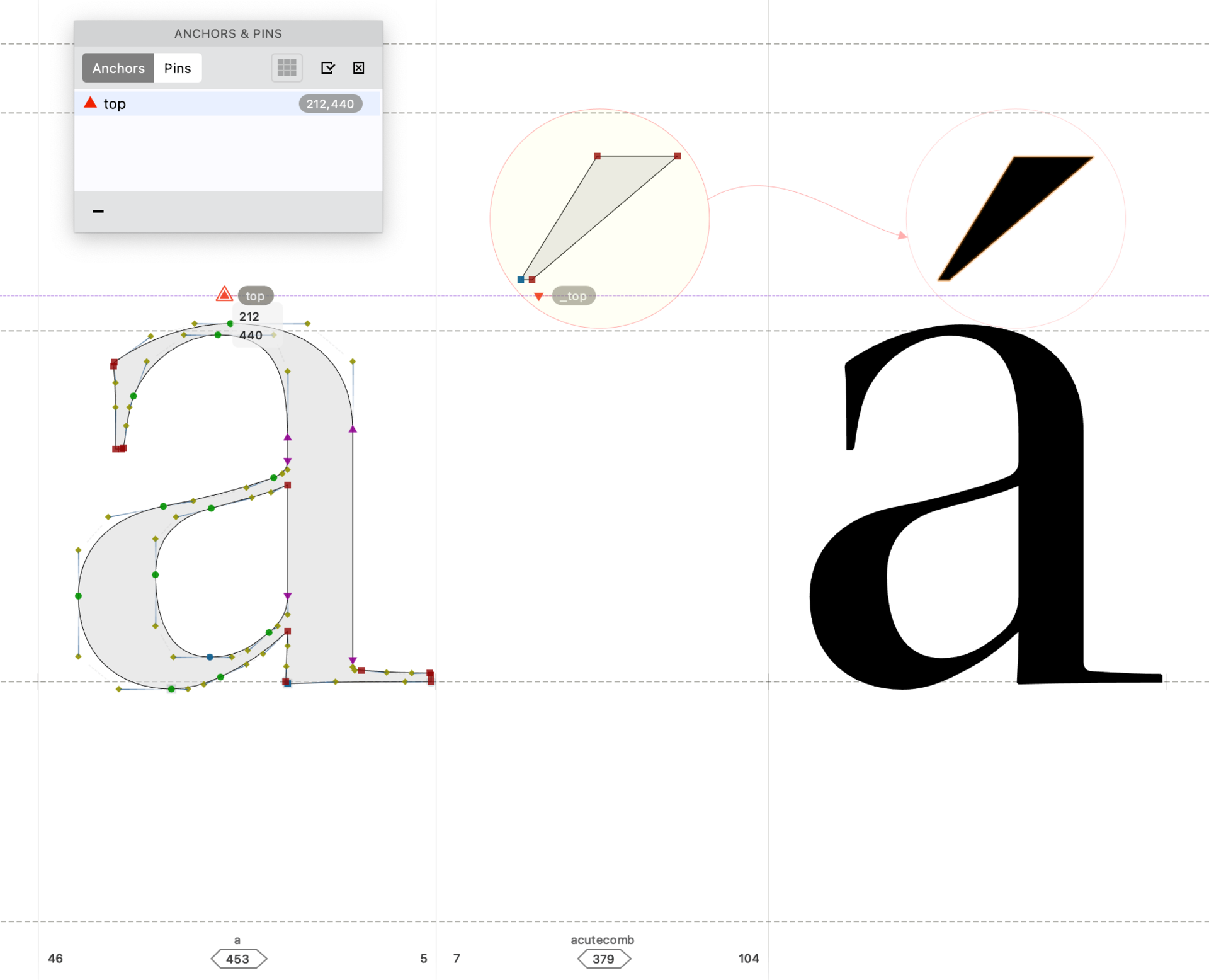

Next, create the composite glyph that combines a letter and the mark, like “á”: Font > Add Glyphs, choose Uppercase Letter or Lowercase Letter, select the cell you need and click OK. If your font already has “a” and “acutecomb” (the acute accent mark), FontLab will create the composite glyph named “aacute” for the letter “á”. The glyph will have the “a” as the base component and “acutecomb” automatically centered above it. Any future changes you make to “a” or “acutecomb” will update the composite.

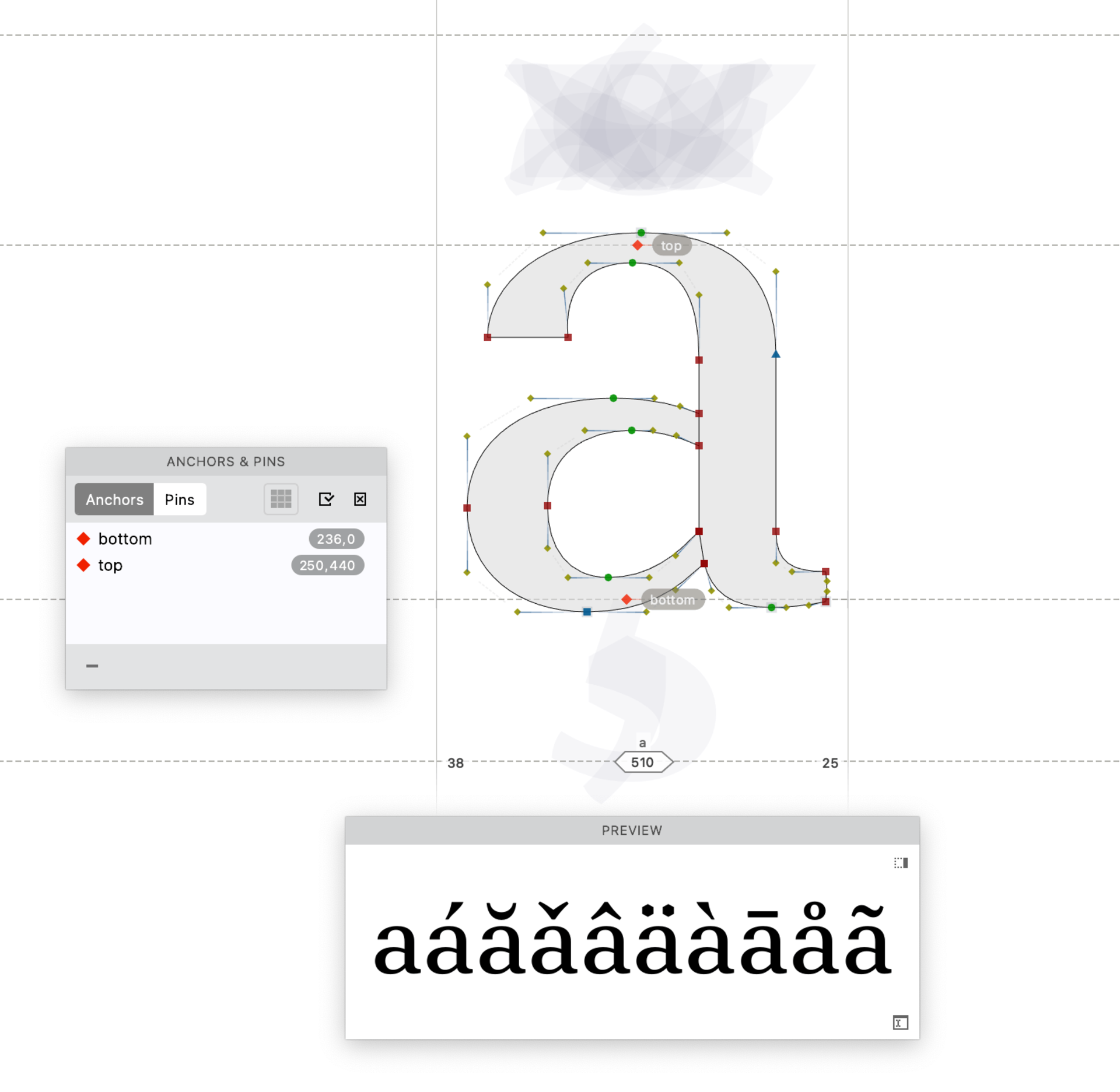

If you’re adding more accented letters, you can use anchors and auto layers to automate the positioning. In the “a” base letter, Shift-click with the Guides tool to add the anchor named “top”. Then in the acutecomb mark, add the corresponding anchor named “top”: the underscore-prefixed name creates the correspondence. For “aacute”, turn on _Glyph › Auto Layer, and the mark component snaps to the base component in the place where the two corresponding anchors meet.

If you create multiple Auto Layer accented glyphs using “acutecomb” (ćéíńóśúź), and then move the “_top” anchor in “acutecomb”, the accent will move in all of them. Moving the “top” anchor in the “a” will shift the mark in all accented variants like àáâäãå.

FontLab’s anchors and auto layers are a great way to assemble accented letters. Try then next time you’re missing a diacritic.